Light vs. Dark

One of the central and most widely used theses in literature is the idea of a battle between good and evil. It could be waged with blades and bullets, or through a battle of sharp wits and razor tongues. These two sides clash over and over, and so many times we will see them indicated by the idea of light versus darkness. Light is good, virtuous and just. It is pure, an angel decked out in gleaming white robes, or a doctor in an unblemished gown. Darkness is sinister, violent and evil. It is corrupt, an ashen demon eager to tear apart all who stand in its way or as an assassin wreathed in a dark suit.

It has always served as an easy way for us to distinguish between what is “good’ and what is “bad”, but with this compartmentalization and labeling come rather entrenched ideas of racial relationships and dynamics. For a long time, societies have looked upon pale and white skin as being better than darker skin. You can see comparisons being draw between dark skin and “dirtiness” or lack of civilization. It ties closely into the idea of otherness that we’ve talked about before, and it has roots in centuries of literary history. Read More…

The Appearance of Heroes

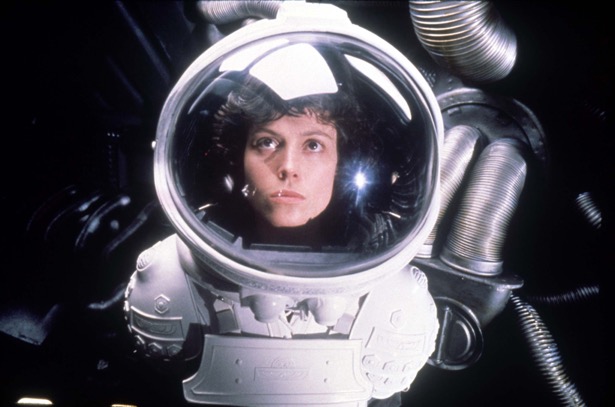

If you are an avid consumer of media, you might have noticed a few things. We write a lot about common tropes and themes that you encounter so you can begin to notice more details. So let’s do a small exercise: when you picture a hero, what do you see? Strong, virtuous, noble, upstanding. Or it is a generic white guy with five o’clock shadow and a set of rocking abs.

For some reason, a lot of our heroes look remarkably similar. Handsome, male, in-good shape, well-dressed, etc. And over the years, this image has changed slightly. It’s why a Victorian era hero looks different than the massive bodybuilders that were 80’s action heroes, and the slightly older, bearded men of today. But some things have stayed the same regardless: the fact that our heroes are overwhelmingly male, white, and heterosexual.

The Noble Savage

As a follow-up to our discussion on “The Other”, let’s look at a more idealized version of the same concept that is popular within literature, books, movies, and games to this day. The Noble Savage is the audience’s idea of an outsider. It is the romanticized depiction of a character untouched by the ills of modern society. They embody the traits that we idealize while at the same time being utterly foreign to us. Read More…

The Other

We’ve talked about the Other and bothering before, but it is a topic that deserves further examination. The Other is all about setting up the relationship within a story, about creating conflict and division. And it can be used in multiple different ways. It is a rather simple idea as well. The other is different. They don’t belong. They are strange and don’t fit in for some reason. It could be any number of things: their race, gender, sexuality, nationality, religion, class, species. Anything that differentiates them from the norm as defined by the story and it’s protagonists. Read More…

The Tragic Hero

When we are looking at the construction of a character, it can help to understand some of the basic archetypes that many authors pull from. We recently talked about Shakespeare as a cultural touchstone, and if we look at many of his plays, we can find evidence of a “tragic hero”. The tragic hero is an age old character archetype describes by Aristotle as:

“A man not pre-eminently virtuous and just whose misfortune, however, is brought upon him not by vice and depravity but by some error of judgement, of the number of those in the enjoyment of great reputation and prosperity; e.g. Oedipus, Thyestes, and the men of similar families. The perfect Plot, accordingly, must have a single, and not (as some tell us) a double issue; the change in the hero’s fortunes must be not from misery to happiness, but on the contrary from happiness to misery; and the cause of it must lie not in any depravity, but in some great error on his part; the man himself being either such as we have described, or better, not worse, than that.” (The Aristotelian Concept of the Tragic Hero) Read More…

The Hero's Journey

We try to give our audience as strong of a background in the themes and ideas that we talk about in our essays. As we look at media of all types, we can see so many common themes that run through our canon, our comprehensive body of work. The more media that you start to consume, the more common threads that you will begin to notice. Perhaps the most common is that of the "Hero's Journey". In essence, the Hero's Journey is a quest that a main character goes through to undergo some kind of personal growth. Harboring deep ties to Arthurian legend, you can see the same set of plot points and character archetypes instilled in so many of the stories that we tell.

You have your main character. Maybe they are a noble knight, or a chosen warrior, or some kid who doesn't quite know their place in the world. They have a specific goal: conquering a dungeon, defeating a dragon, or just talking to a pretty girl in gym class. All along the way they are faced with challenges that stimulate the growth of the character not only in strength of body, but also of character. It is the classic coming of age tale that is told in so many ways by so many different people. Read More…

Male Gaze

When we talk about the depiction of sex and sexuality, frequently the idea of the “Male Gaze” comes up, mostly in regard to female characters and their depiction. At its heart, it’s a rather simple concept, but it can reveal a lot about the intended audience of a piece and of who made it. The Male Gaze is how a scene is portrayed specifically to be attractive to a heterosexual, male audience. It’s designed to appeal to men, and it is evidenced through the difference in depictions of straight male characters, straight female characters, and lesbian female characters and their relationships in media. Read More…

Tokenism

As a follow-up to our discussion on the Noble Savage, I wanted to take the time to talk about the delicate issue of tokenism in contemporary media or literature. Put simply, Tokenism is the idea of diversity being included for show, of including minority characters in minor roles such that a single minority character has to represent the entirety of their group.

In less malicious contexts, this can take the shape of something that you might see on a brochure, a “multicultural” group of people that are diverse in appearance only. These characters are not allowed to express themselves in a way that would significantly differentiate them from the norm (read: white and straight). It is a way for studios to brag about embracing diversity without actually doing anything of substance. Read More…